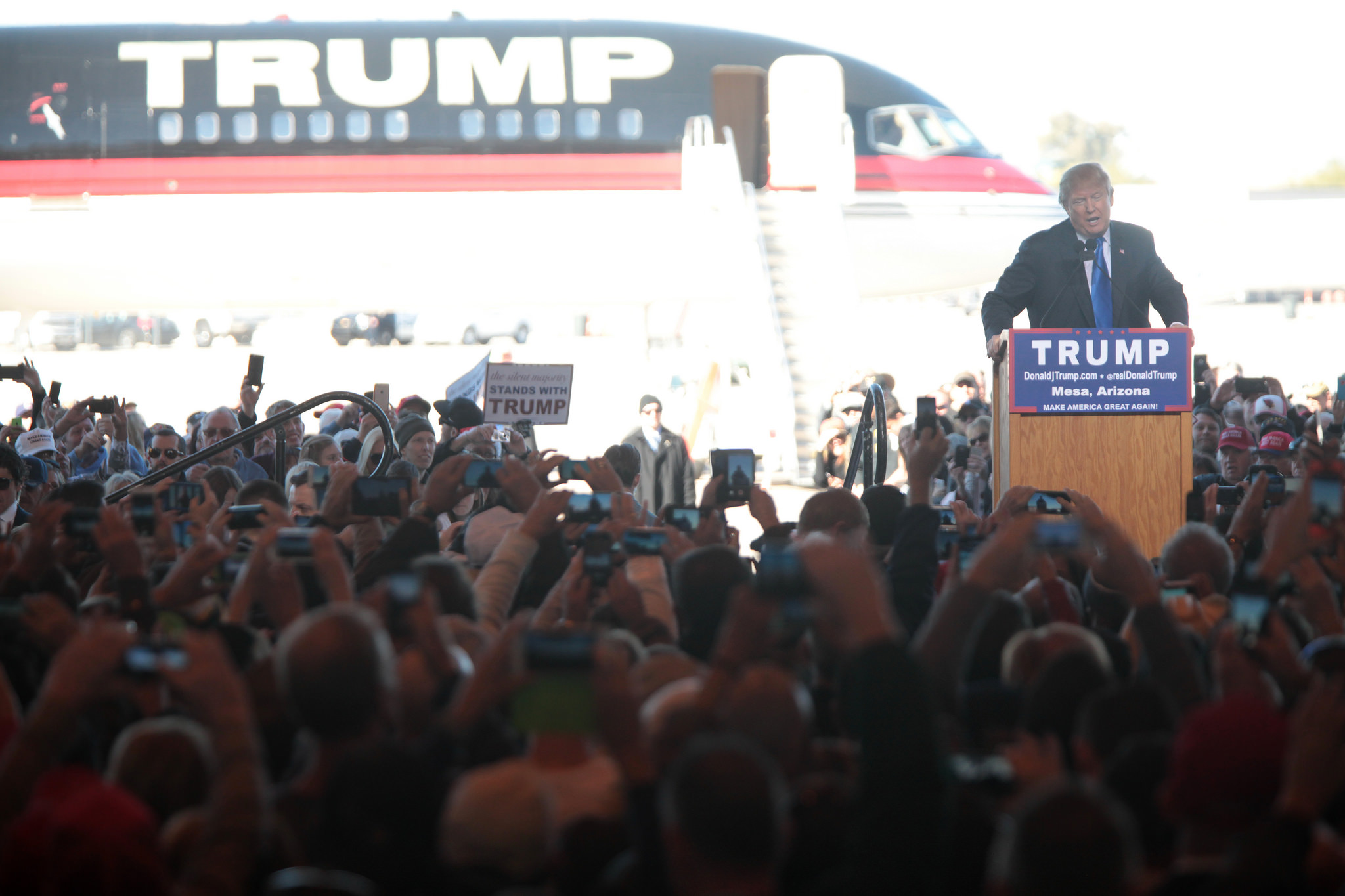

Among the many surprising aspects of the recent Presidential election was the extent to which anger with international trade agreements motivated voters. Bernie Sanders railed against free trade as he pursued the Democratic nomination and Donald Trump's supporters seemed even angrier. This rejection of the goal of tariff-free international movement of goods, however, represents a sharp departure from roughly eighty years of bi-partisan support for free trade. This month historian Aaron Cavin exlains why that consensus seems to have fallen apart.

Throughout his campaign for the presidency, Donald Trump held up Carrier, an air conditioning and heating company, as a symbol of the plight of American manufacturing, buffeted by free trade deals that hurt American workers. The company had planned to close an Indiana plant that makes furnaces, shifting production to Mexico and leaving 1,400 American workers jobless. Trump vowed to prevent that from happening.

For Trump, bringing Carrier to heel was part of a broader pledge to stop the offshoring of American manufacturing jobs. To revive American industry, Trump has promised high tariffs on goods from Mexico and China, and he has inveighed against trade agreements, particularly the North American Free Trade Agreement (PDF File). “NAFTA,” declared Trump, “is the worst trade deal maybe ever signed anywhere but certainly ever signed in this country.”

As a sign of his commitment against “unfair” trade deals, Trump vows that, on his first day in office, he will withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Not since Herbert Hoover has an American presidential figure so roundly rejected free trade.

Yet what is even more striking is that Trump’s opposition to trade agreements appeared widely shared among Democrats. In his campaign for the Democratic nomination, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders denounced NAFTA and TPP. “I think they have been a disaster for the American worker,” said Sanders. When asked if there was a single trade agreement that he liked, in all of American history, Sanders’ answer was simple: no.

The anti-trade mood pushed Hillary Clinton to withdraw her previous support for TPP, which she had once lauded as the “gold standard” in trade deals.

Trade has clearly become a central preoccupation of millions of Americans. While there have been critics of U.S. trade policy for some time, the scope of the current debate is new.

For more than half a century, there has been a bipartisan consensus around free trade. Leaders of both major political parties and the majority of Americans have appreciated the jobs, goods, and prosperity brought by international trade.

But today that consensus appears to have shattered. How did a bipartisan consensus emerge supporting free trade? Why is it now collapsing? And what will this mean for the American economy?

A Vision of Global Free Trade

The roots of our contemporary debate go back to the aftermath of World War I. The devastating war reflected the breakdown of the economic order of the late 19 th century, when massive numbers of goods and people flowed across national borders. The war marked the end of a half-century during which the world was, in some important ways, more economically integrated than it is today.

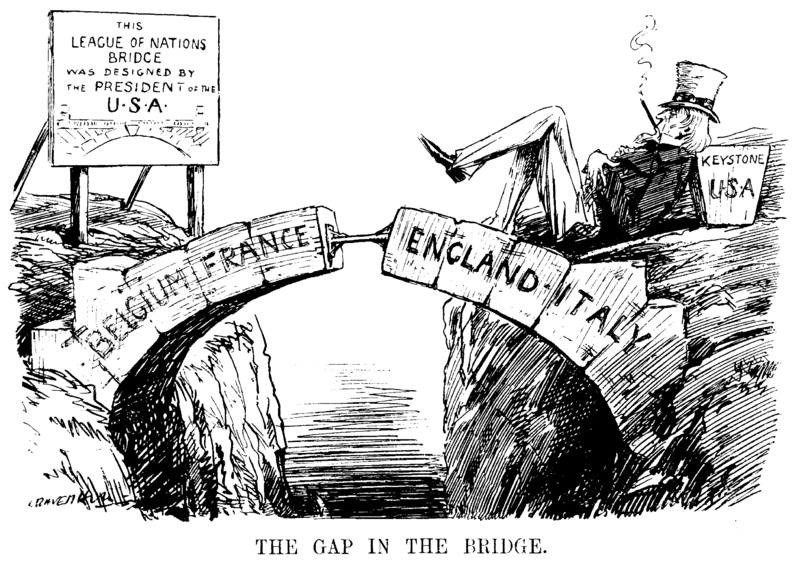

As the war came to an end, President Woodrow Wilson hoped to resurrect global trade through new international institutions. In his Fourteen Points speech, Wilson called for “the removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers” to trade. He proposed a League of Nations, a community of sovereign nation-states that would resolve disputes peacefully and facilitate free trade and open markets.

But Wilson, a Democrat, faced opposition from a Republican-controlled Congress. The Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles—itself a far cry from Wilson’s vision of peaceful and equitable cooperation—and the United States failed to join the League of Nations. Wilson suffered a stroke after traveling 9,981 miles in a vain attempt to win public support for the treaty, and soon thereafter Republicans captured the presidency and held it for the next 12 years.

With a solid hold on the national government, the GOP rejected Wilson’s internationalism and pursued, in the words of the party’s 1920 platform, “national greatness and economic independence.” Congress raised tariffs and praised American business, striding blithely into the worst economic crisis of the twentieth century: the Great Depression.

Trade in the Great Depression

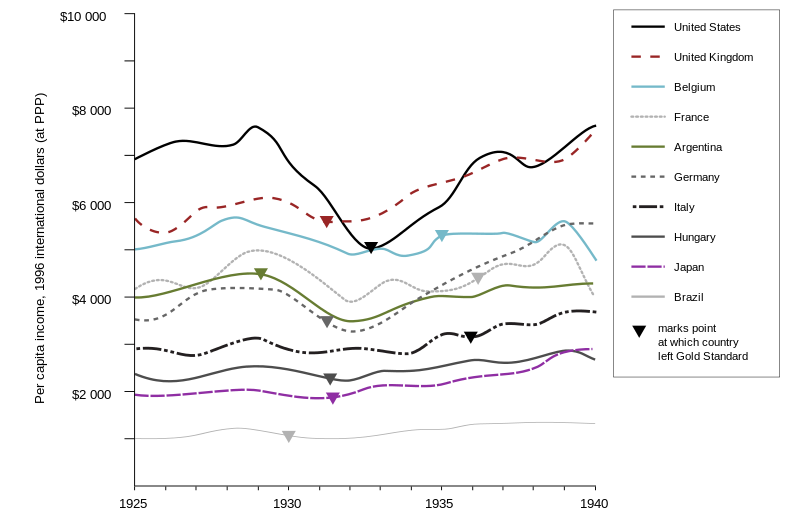

Partisan differences on trade peaked during the Depression. The Republican-controlled Congress responded to the economic crisis with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which raised tariffs to the highest level in 100 years, in an effort to protect American jobs and farms from foreign competition.

Yet America's trading partners followed suit, instituting their own tariffs. The cumulative effect was a disaster: American imports and exports dropped by almost two-thirds.

Smoot-Hawley had passed on near party-line support, and the next election ushered in one of the greatest partisan shifts in American history. When Franklin Roosevelt and the Democratic Party swept into power in 1932, they offered a different approach: the Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act of 1934. In the flurry of New Deal legislation, the RTA is often overlooked, yet it constituted a watershed in trade policy.

Traditionally, Congress had determined tariffs unilaterally, generally in response to lobbying from business constituencies. But with the RTA, Congress ceded to the president the authority to negotiate tariffs. By shifting this power to the presidency, tariffs became one part of the nation’s foreign policy. The result was a dramatic reduction in tariffs.

While the act primarily affected trade between the United States and Latin American nations, it laid the institutional foundation for America to pursue a global free trade regime and initiated 80 years of trade liberalization.

But while the United States and Latin American nations increased trade in the 1930s, much of the world headed the opposite direction. Great Britain sought to protect homegrown industries; France doubled its tariffs. Nazi Germany established a policy of autarky, striving for self-sufficiency by replacing imports with domestic production—a policy that reached its horrifying conclusion in the synthetic rubber factories of Auschwitz.

The collapse in trade among nations in the 1930s accompanied a rise in aggressive militarism, leading inexorably into World War II.

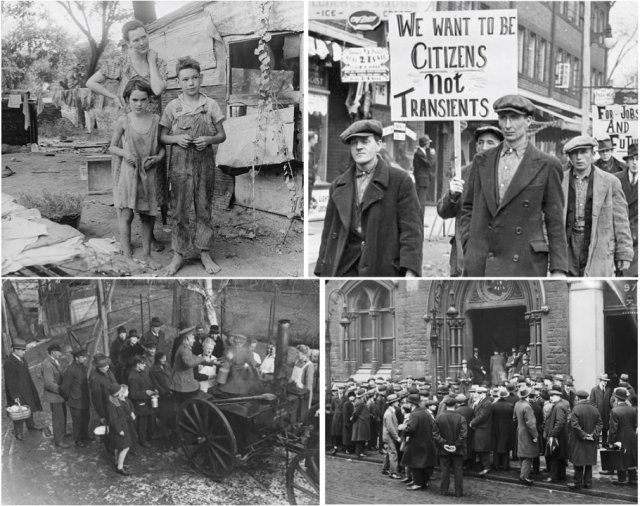

A poor Oklahoma family in 1936 ( top left ). A protest against unemployment in Toronto, Canada around 1930 ( top right ). The German Army feeding the poor in 1931 Berlin ( bottom left ). Unemployed people in front of a London workhouse in 1930 ( bottom right ).

The Postwar Order

In 1938, as he watched economic nationalism slide into war, Secretary of State Cordell Hull reasoned, “Our nation, and every nation, can enjoy sustained prosperity only in a world which is at peace; a peaceful world is possible only when there exists for it a solid economic foundation, an indispensable part of which is active and mutually beneficial trade among the nations.”

For Hull, trade was essential for peace. When he won a Nobel Peace Prize in 1945, the awarding committee summed up Hull’s thinking this way: “High tariffs are barriers obstructing the development of trade and friendship between nations, thereby becoming barriers also to lasting international peace.”

Hull’s vision inspired a range of international institutions, most famously the United Nations, designed to preserve peace in the postwar world. But alongside the UN came new economic institutions as well: the World Bank, which would finance large-scale reconstruction and economic development projects, and the International Monetary Fund, which would stabilize and manage currency exchange rates.

While plans for an International Trade Organization stumbled—in large part due to Republican opposition in the U.S. Congress—in 1947, after seven months of negotiations, 23 nations signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. The GATT substantially lowered trade barriers; signatories committed to 45,000 tariff concessions.

What accounts for such sweeping changes in the international economic order?

American policymakers, particularly in the Democratic Party, believed that nationalist economic policies had led to global depression and world war. By pursuing only their own interests, each nation had enacted policies that harmed other nations. These beggar-thy-neighbor policies, however, ultimately made things worse for everyone. Economic nationalism produced an international crisis.

As Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau explained in 1944, at the close of the conference in Bretton Woods (PDF File), New Hampshire, that established the postwar economic system, the “only genuine safeguard for our national interests lies in international cooperation.”

American prosperity depended upon the prosperity of other nations. Prosperity, in turn, prevented war. Mutually beneficial trade thus became a national security issue.

Explaining the need for international trade, President Harry Truman put it simply: “We must not go through the thirties again.”

The Birth of the Free Trade Consensus

But could the international free trade regime hammered out after World War II survive American partisan politics? Would trade liberalization fall prey to the economic nationalism that scuttled Wilson’s vision after World War I?

After all, the Republican Party had been the party of Smoot-Hawley. Ohio Senator Robert Taft, leader of the isolationist wing of the Republican Party, compared American support for the IMF to “pouring money down a rat hole.” In 1936 and in 1940, the Republican Party platform vowed to repeal the tariff reductions and raise tariffs once again.

But when the GOP won back Congress in 1946, they quietly shelved plans for a repeal. When Republican Dwight Eisenhower won the presidency—the first Republican to do so since Herbert Hoover—he not only endorsed the trade policies established by Roosevelt and the Democratic Party, but demanded their expansion.

In his 1958 State of the Union address, Eisenhower declared that free trade was “both in our national interest, and in the interest of world peace.” The line could have come from Cordell Hull.

By the 1950s, most Republicans had joined the free trade consensus. Why? The answer lies in the unique circumstances of the postwar world.

World War II had decimated America’s major trading partners; the European and Japanese economies had collapsed. In this context, American manufacturers saw trade liberalization less as a threat than an opportunity. Free trade enabled businesses to export their goods to willing buyers while facing little competition from imports. With major business constituencies eager for trade, Congressional representatives obliged.

These economic circumstances coincided with a geopolitical crisis: the dawn of the Cold War. Most American policymakers, regardless of party, saw trade as a way to incorporate other nations into the capitalist “free world” led by the United States, thereby limiting the reach of the USSR. In the global competition for allies and resources, trade policy was an essential part of foreign policy.

While business opportunities and national security attest to the role of self-interest in American trade policy, there was an altruistic aspect as well. In the decades after World War II, the United States was by far the world’s largest economy, and many Americans agreed on the nation’s moral responsibility to help others through economic development. For them, international trade went hand in hand with foreign aid, cultural exchange, and programs like the Peace Corps, all forging a world of shared prosperity.

Cracks in the Consensus: The North American Free Trade Agreement

The free trade consensus persisted for decades, benefitting from periods of remarkable economic growth and weathering occasional insurgencies from disaffected workers (notably, autoworkers during the surge of Japanese automobile imports in the 1970s and 1980s). But cracks in the consensus emerged with passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (PDF File) in 1993.

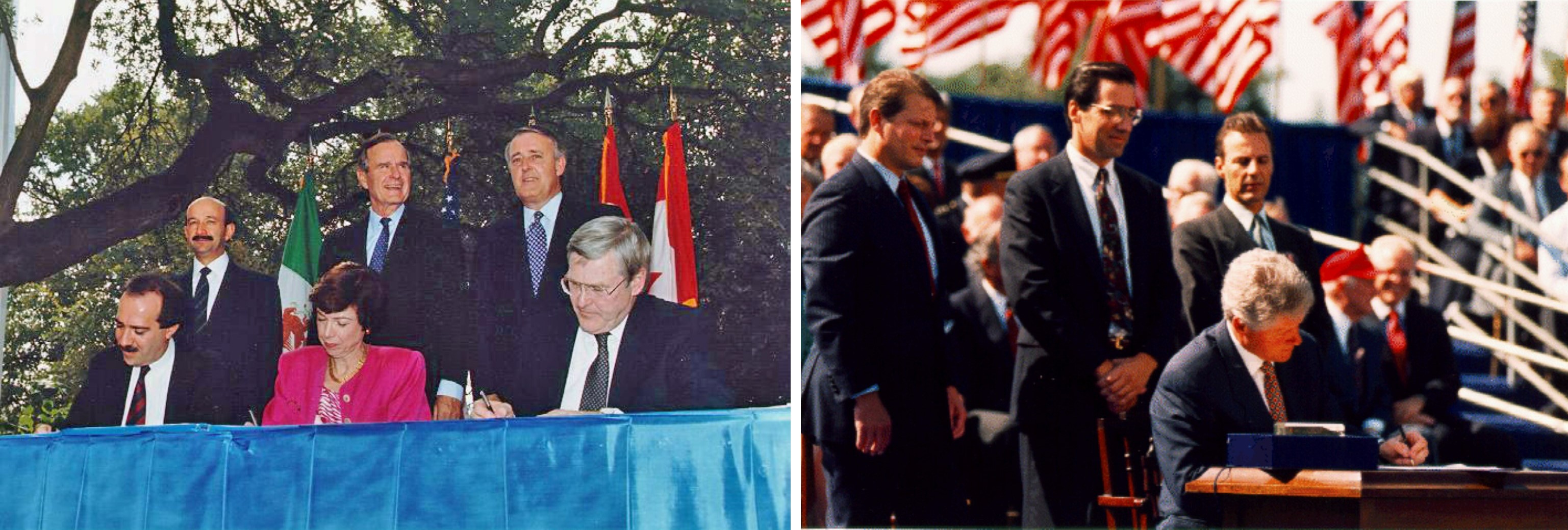

Developed under the administration of Republican George H.W. Bush and signed by Democrat Bill Clinton, NAFTA represented the bipartisan consensus on free trade. The agreement established a vast free trade zone among the United States, Mexico, and Canada. The main proponents were businesses eager for cheap labor and the economies of scale made possible by the continental common market, enabling them to compete more effectively against the business giants of the European Union and Japan (PDF File).

Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, President George H.W. Bush, and Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney stand in the back as their trade and economic representatives sign the draft of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1992 ( left ). President Bill Clinton signing NAFTA in 1993 (right).

Public debate over NAFTA ended the era of popular acquiescence that had accompanied trade deals since 1945. Unions had backed free trade throughout most of the postwar decades, but every major union in the United States opposed NAFTA; unions in industries that faced foreign competition, including steelworkers, autoworkers, clothing workers, and Teamsters, were particularly strident.

A key constituency of the Democratic Party, unions had supported Clinton in his 1992 presidential campaign, but Clinton paid little heed to their objections. He dismissed their criticisms in a speech on NAFTA and further trade agreements, contending, “There is no alternative.”

The architects of NAFTA fully realized that there would be large numbers of job losses in U.S.-based manufacturing, but they expected that better jobs would replace them. As Clinton explained, “Good jobs, rewarding careers, broadened horizons for the middle class Americans can only be secured by expanding exports and global growth.”

And over the next decade, while NAFTA-related job losses in the United States reached up to 2 million (economists offer widely competing estimates of the impact of NAFTA on American employment), the American economy overall added 34 million jobs. While many of these were high-tech jobs in the “new economy” heralded by Clinton, millions were in low-wage services and retail. Workers laid off due to NAFTA typically found work that paid less than their previous jobs.

At any rate, for the Clinton administration, and the Bush administration before it, NAFTA was about more than American jobs. Like the policymakers who established the postwar international economic system, Clinton believed that free trade was essential for American security.

Clinton placed NAFTA in the grand tradition of global economic integration, from Woodrow Wilson’s vision to the IMF, the World Bank, and the GATT. Upon signing NAFTA, Clinton echoed these forebears, claiming, “Our national security … will be determined as much by our ability to pull down foreign trade barriers as by our ability to breach distant ramparts.”

U.S. leaders especially believed that a stronger Mexican economy would benefit Americans, and not just because Mexico was one of the largest importers of American goods. Regardless of NAFTA, the United States was willing to spend billions supporting Mexico to prevent having a failed, and thus unstable, state on its southern border. (Indeed, the Clinton Administration orchestrated a $20 billion bailout of the Mexican economy in 1995 to address the nation’s currency crisis.)

If NAFTA helped Mexico’s economy, even at the expense of U.S.-based manufacturing, it would ultimately be good for the United States.

The Battle of Seattle: The World Trade Organization

After signing NAFTA, Clinton immediately turned his attention to an even larger free trade project: the World Trade Organization. The WTO was an evolution of the GATT, hammered out in the Uruguay Round, a lengthy and complex set of trade negotiations that lasted from 1986 to 1994.

The Uruguay Round featured a multitude of competing objectives: developing nations pressed for a liberalization of agricultural trading, a proposal long resisted by the United States and European Union; the United States wanted more protections for services and intellectual property; all countries realized that the GATT had largely succeeded in reducing tariffs, and now the largest obstacles to trade were non-tariff barriers.

After long years of negotiations, countries struck a grand bargain, aiming to address all these concerns. In 1994, 123 nations signed a new agreement, and the WTO went into effect the following year.

The WTO unleashed even more unrest than NAFTA. In 1999, tens of thousands of protesters disrupted the WTO conference in Seattle. “The WTO is a mistake,” thundered Teamsters president James Hoffa to a crowd of 20,000 union members in Seattle. Corporations were writing the rules of the global economy without any input from workers. “We will have a place at the table of the WTO,” Hoffa said, “or we will shut it down.”

Seattle Police spraying opponents of the World Trade Organization (WTO) with pepper spray in 1999 ( left ). A sign from the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle, Washington depicting the WTO as the Grimm Reaper stepping on the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and Endangered Species Act ( right ).

There had never been such violent opposition to trade deals in the United States, nor such a diverse coalition of opponents, including trade unionists, environmentalists, consumer advocates, religious groups, and even internationalists frustrated that globalization had not lived up to its promises.

The WTO, they argued, spurred competing nations to dismantle environmental and labor regulations in a “race to the bottom,” enriching global corporations at the expense of workers both North and South. The scale of the protests surprised nearly everyone. The unrest was put down by tear gas and the National Guard, but the “Battle of Seattle” revealed deep discomfort with the prevailing global economic order.

The Consensus Collapses: The Trans-Pacific Partnership

With the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the bipartisan consensus finally cracked.

The TPP would create a free trade region around the Pacific Rim, stretching from Chile and Peru in South America through the United States, Mexico, and Canada, across the Pacific to Japan, through the South China Sea nations of Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Brunei, down to Australia and New Zealand. With 800 million people and 40 percent of the world economy in the TPP, it would be the largest regional trade agreement in history.

Started by Republican president George W. Bush and advanced by his Democratic successor Barack Obama, the TPP appeared to follow the bipartisan pattern of earlier trade treaties. Under its terms, the TPP offered increased American export opportunities, particularly for agriculture, beef, pharmaceuticals, and high tech. As with trade agreements in the past, the TPP was endorsed by the main American business lobbies, the National Association of Manufacturers, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and the Business Roundtable.

For the Obama Administration, the value of the TPP was partly strategic. Just as previous administrations used trade policy to advance their foreign policy agendas, the Obama administration envisioned the TPP as a bulwark against Chinese influence in the Pacific and Southeast Asia. The agreement would expand the role of the United States in the region, a key part of the administration’s “pivot to Asia.”

Critics charged that the TPP was “NAFTA on steroids”—a revealing insult in that “NAFTA” had become an epithet. Negotiators of the agreement aimed to prevent the resistance that accompanied NAFTA and the WTO by specifically protecting health, environmental, and labor regulations. Members would be required to recognize unions, establish minimum wages, prevent child labor, and promote workplace safety.

But critics contended that the TPP’s mechanism of dispute resolution—Investor-State Dispute Settlement, which allows foreign corporations to sue member governments—effectively prohibited regulation in the public interest. Defenders of the treaty countered that the United States already uses ISDS in 51 trade agreements, including NAFTA, and that of the 17 ISDS suits brought through NAFTA, the United States has lost none.

Equally disturbing for critics was the secrecy that shrouded the TPP negotiations. Negotiations were classified, and while the Obama administration appointed hundreds of advisors to assist in the process, the overwhelming majority of advisors came from businesses and trade associations, with only modest participation from labor and environmental groups.

Sherrod Brown, the Democratic Senator from Ohio, assailed the lack of transparency: “This continues the great American tradition of corporations writing trade agreements, sharing them with almost nobody, so often at the expense of consumers, public health and workers.”

The specter of job losses through the TPP and other agreements has spurred political polarization around issues of trade. According to a Pew survey in March 2016, a bare majority of Americans say that free trade agreements are good for the country.

A 2012 protest against the TPP in Leesburg, Virginia ( top left ). A 2015 protest against the TPP in Washington, D.C. ( top right ). Opposition to the TPP at the March for Clean Energy Revolution in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 2016 ( bottom left ). A 2014 protest in Seattle, Washington against the TPP ( bottom right ).

Yet the survey revealed a partisan difference in attitudes. While most Democrats supported free trade agreements, most Republicans opposed them, especially among Trump supporters, 67 percent of whom said that free trade was bad for America. The partisan divide paralleled racial, gendered, and age divides. White men older than 65 were the staunchest opponents of free trade, while most Latinos, African Americans, women, and younger people were the most likely supporters.

As the survey indicates, the contemporary conversation on trade takes place within the narrow boundaries of what is good for the United States. Most Americans are unmoved by the U.S. trade representative’s affirmations that the TPP will end child labor in Vietnam or strengthen unions in Brunei—a line of argument that would have been compelling as recently as the 1990s but that today seems impossibly quaint.

Gone entirely is any sense that the United States—still the world’s largest economy—has any moral responsibility to alleviate poverty elsewhere, or that American workers might find common cause with workers in other nations.

Popular hostility has tempered politicians’ enthusiasm for trade agreements. While most Republicans and Democrats in Congress favored the TPP, the agreement quickly became politically toxic, and even supporters of the agreement rarely vocalized their support. By May 2016, all remaining contenders for the presidency had come out against it.

Despite Obama’s urging, Congress appears unlikely to move on the bill. For the first time in recent history, a landmark trade agreement, years in the making, appears headed for defeat.

The Rise of China

The contemporary anxiety about trade parallels the rapid increase in imports from China. After a series of economic reforms initiated in 1978, China pursued export-oriented development. The Chinese Communist Party facilitated a breakneck expansion of capitalism, aggressively recruiting multinational corporations to invest in the nation’s manufacturing sector.

U.S. trade with China steadily increased through the 1980s and 1990s, and in 2000, after 13 years of negotiations, the United States established Permanent Normalized Trade Relations with China. China joined the WTO the following year.

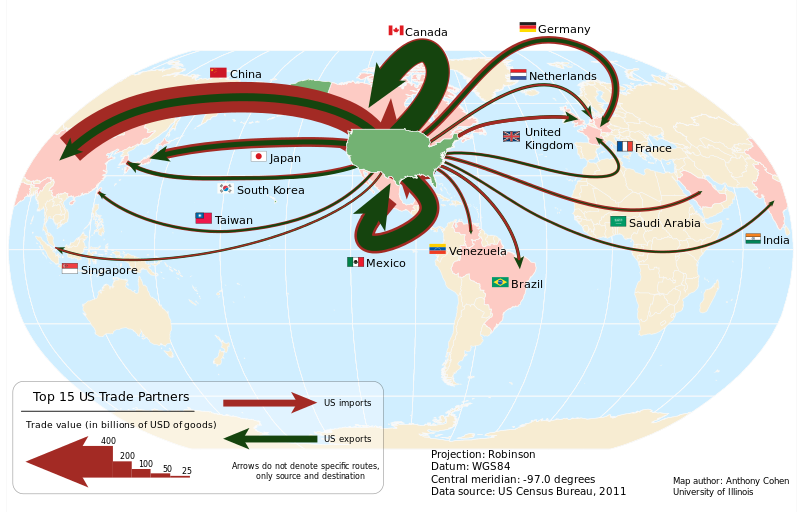

China quickly became one of America’s largest trading partners. Within five years, imports and exports tripled; within a decade, U.S. exports had quintupled and imports quadrupled. U.S. service exports to China increased 791 percent, giving the United States a trade surplus in services. Outweighing the trade surplus is a mammoth trade deficit in goods—a record $356 billion in 2015.

Among the principal beneficiaries of increased trade with China have been American retailers, and none more than Walmart. Walmart’s drive for “everyday low prices” led the company to invest heavily in China, where low labor costs coincided with a stern government that guaranteed political stability, a stable currency, and efficient shipping infrastructure. Today, Walmart imports more goods from China than do the entire nations of Germany, the United Kingdom, or Russia.

Ostensibly a retailer only, Walmart directly or indirectly controls a gargantuan network of factories, sweatshops, and subcontractors in China.

The heart of this industrial behemoth is Guangdong Province, a rapidly urbanizing stretch of the South China Sea coast. In hundreds of thousands of factories, workers toil 12 hours a day, six days a week, for as little as $100 per month. Still, the wages are high enough to draw tens of millions of migrants from rural villages in inland China.

Workers in electronics factories in Guangdong Province in 2013 ( left ) and 2005 ( right ).

Migrant workers, however, lack legal residency status, which makes them easily exploitable. Walmart, the largest retailer in the United States, relies upon these workers to produce the electronics, clothing, and cheap consumer goods that line the company’s shelves.

The Long History of Industrial Decline

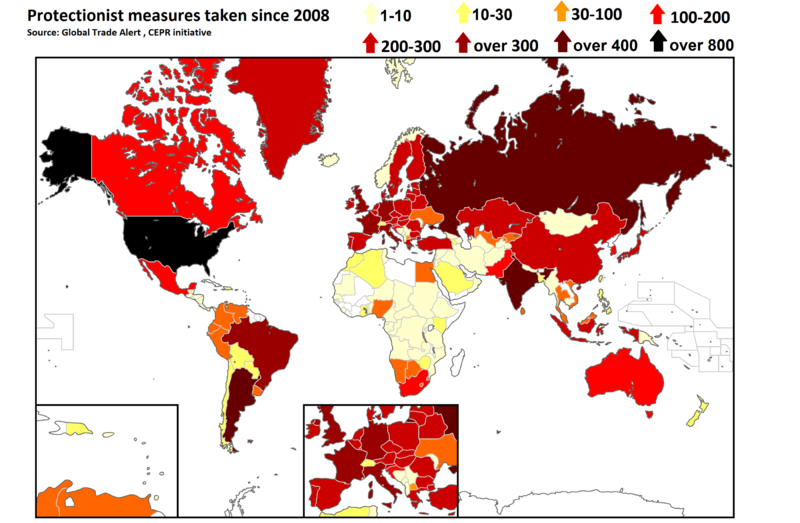

China is Trump’s main villain in his narrative of American decline. China, he said, is “killing us on trade” and “raping our country.” The trade deficit constitutes the “greatest theft in the history of the world.” Trump’s solutions—rip up the trade deals and slap a 45-percent tariff on goods from China—harken back to the economic nationalism of Smoot-Hawley.

Such actions are unlikely to “bring back” well-paying manufacturing jobs to struggling communities in the Rust Belt. The decline of manufacturing in the great cities of the industrial heartland—Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and many more—began not in 2001, when China joined the WTO, nor in 1994, with the advent of NAFTA, nor even in the 1970s, when Japanese automakers increased their share of the American market.

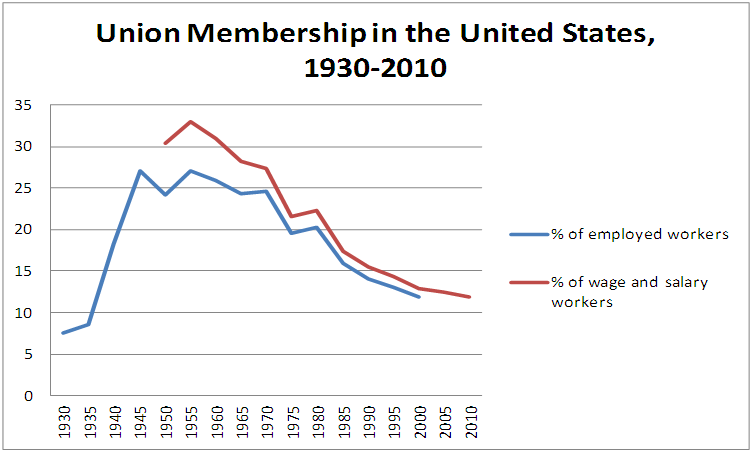

It began in the 1950s, as businesses moved production from the urban centers of the upper Midwest, first to the suburbs, then to the rural Midwest, and eventually to the states in the South and West, in a relentless drive to lower wages, eliminate unions, and increase returns. The move to China is only the most recent episode in a decades-long search for a tractable workforce.

Meanwhile, it will surprise many to learn that manufacturing’s contribution to the American economy has increased substantially from $63 billion in 1947 to more than $2 trillion in 2015 (in constant dollars). In spite of competition from Mexico and China, American manufacturing output has doubled over the past 30 years.

Manufacturing constitutes the fourth-largest sector of the American economy. Over the past five years, American factories have even added 600,000 jobs. Nevertheless, American manufacturing employs millions fewer workers than in the past, due in large part to the automation of jobs that were once done by hand. And automation will only further reduce employment in the future.

Since 2003, there have been more jobs in retail than in manufacturing. Today, some 16 million people work in retail, 1.4 million of them at Walmart alone. If Trump slaps tariffs on imports from China, Americans will have to pay higher prices for clothes, toys, electronics, and more. Many Americans, surely, will grudgingly pony up an additional $300 for an iPhone, but millions more will resent paying nearly twice as much for basic consumer goods.

High tariffs would force Americans to confront an abiding tension between their roles as producers and as consumers, a reckoning they are unlikely to handle gracefully.

Inequality and the Future of Trade

An unusual feature of today’s opposition to trade is that it comes not in the depths of a great depression but during a historic expansion, a time when unemployment is low and falling.

Yet the benefits of that expansion have not been shared equally. Those who have suffered most from plant closures are concentrated in certain places with few alternative jobs, and they have limited resources or little will to move to areas where employment is growing.

The increase in economic inequality has fostered hostility to China and to global engagement more broadly.

A t-shirt for supporters of President-Elect Donald Trump's 2016 campaign."Build the Wall" was a common rallying cry for many Trump supporters who opposed immigration from Mexico.

But the real causes of inequality are not foreign competition; they are public policies. Nations have a remarkable range of policy options in response to increased trade, and while most other OECD nations (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) accept a higher percentage of free trade, they have much less inequality.

In the United States, it is far easier to blame foreigners for stealing jobs than it is to address inequalities of wealth and power at home.

The bipartisan consensus for an integrated global economy developed in a unique and irreproducible context. Besides recent experiences of the Depression and global war, America’s unparalleled economic power in the postwar era coincided with union strength, social supports, and an aggressive tax structure that reduced inequality.

Domestic support for further trade agreements likely will not be forthcoming until more is done to alleviate the dislocations caused by trade liberalization. Neither will domestic support be forthcoming without a seat at the table. The rallying cry of WTO protesters was “No globalization without representation”—a plea to democratize of the global trade regime.

In the absence of domestic support, the United States will be unable to lead the international order. As the United Kingdom leaves the European Union, and as nationalist uprisings in Italy, France, and elsewhere threaten to undermine the European Union entirely, it is easy to imagine a future with fewer international agreements.

Facing a revival of beggar-thy-neighbor policies, we would do well to remember that cooperation can achieve objectives that nationalism cannot, and that nationalism can lead to situations in which everyone loses.